I love Komga. It’s been my go-to for managing comics, manga, and ebooks for years, and it genuinely does the job well. The UI is clean, the feature set is rich, and the community around it is great. If you self-host a digital reading collection and haven’t tried it, you should.

But after years of daily use, I kept bumping into a few limitations that I couldn’t work around. And eventually, the itch to build something of my own became too strong to ignore.

Where Komga Falls Short (For Me)

Let me be clear: Komga is excellent software, and for most people it works perfectly. My issues are specific to how I want to deploy and organize things.

The first is a database limitation. Komga only supports SQLite, which stores everything in a single file. That’s fine for a straightforward setup, but if you want to run multiple instances behind a load balancer (say, for redundancy or to handle more users) the file-based database becomes a bottleneck. Connection locks prevent concurrent access, so you’re limited to a single instance. Adding PostgreSQL support would solve this, but it was requested and declined by the Komga team.

The second is metadata management. Komga doesn’t support automatic metadata fetching. There’s a separate tool called Komf that can do it, but it requires running an additional server and a script, only supports a handful of metadata providers, and the whole setup isn’t exactly seamless. I ended up publishing custom n8n nodes for Komga and MangaBaka to populate metadata on a schedule. It worked, but it felt like duct tape on top of duct tape.

Lastly is the lack of user ratings and custom metadata. I wanted to rate my series and use those ratings to discover new things to read. Komga doesn’t support user ratings, and there’s no custom metadata field system to hack around it. Both features were requested multiple times but never picked up. I resorted to maintaining an external spreadsheet, which, as you can imagine, I stopped updating pretty quickly.

Third Time’s the Charm

Here’s the part where I have to be honest: this isn’t my first attempt at building a media server.

In 2020, I started a project called “Alx” (short for Alexandria, the legendary library) in Elixir. I got the interesting parts working (data models, file parsing, the core architecture) and then hit the part that always kills my side projects: the tedious stuff. Building out a full frontend, wiring up all the CRUD endpoints, handling edge cases. None of it was hard, just… boring. Motivation faded.

In 2022, I tried again in Go. Same pattern. The exciting parts came together quickly, and then the long tail of “make it actually usable” stretched out in front of me and I lost steam.

Two failed attempts, same root cause. I could build the interesting core, but a side project needs more than a clever backend to be useful, and the grind of finishing everything else kept draining the fun out of it.

So for attempt number three, I made two key decisions that changed the approach entirely.

Decision 1: Pick a Language That Keeps Me Engaged

The previous attempts taught me that the core parsing and architecture work isn’t the problem. I can get that done. The problem is everything that comes after: the frontend, the CRUD endpoints, the polish. That’s where motivation dies.

Go would have been the pragmatic choice since I know it well and the ecosystem is solid. But “pragmatic” didn’t save the last two projects. I picked Rust because I genuinely wanted to learn it, and working in a language that excites me is what keeps a side project alive through the boring stretches.

Decision 2: Rust Core, Polyglot Integrations

Choosing Rust for the core was about motivation, but I also knew from experience that building everything in one language can slow things down, especially for integrations like metadata providers (think ComicVine, MangaDex, AniList, Open Library).

The solution was a hybrid architecture: the core application (file parsing, scanning, the web server, the database layer) is Rust. But metadata integrations follow a JSON-RPC 2.0 protocol over stdio, similar to how MCP servers work. Each integration is a standalone process that Codex communicates with. You can write one in Go, Python, Node.js, or any language you prefer.

This means the community can contribute integrations without needing to know Rust, and I can focus my Rust energy on the parts that benefit most from it: fast file I/O, efficient image processing, and a stateless server that scales horizontally.

Under the Hood: Architecture and Design

The fun part about building a project from scratch is getting to make deliberate architectural decisions. Here are some of the concepts that shape Codex.

Stateless by Design

Every Codex server instance is stateless. Authentication uses JWT tokens, all persistent state lives in the database, and live updates flow through Server-Sent Events (SSE). This means you can put multiple instances behind a load balancer and they all behave identically. No sticky sessions, no shared memory, no coordination between nodes. In practice, this makes Codex a natural fit for container orchestration with Kubernetes or Docker Swarm.

Dual Database Support

Codex supports both SQLite and PostgreSQL from the same codebase, using SeaORM as the database abstraction layer. SQLite is the default for simple, single-instance setups (it requires zero configuration), while PostgreSQL unlocks horizontal scaling and features like cross-container task notification via LISTEN/NOTIFY.

The tricky part of supporting two databases isn’t the query layer — SeaORM handles that well — it’s the operational differences. SQLite needs WAL mode and careful pragma tuning for concurrent reads, while PostgreSQL needs connection pool sizing and SSL configuration. The configuration system handles these transparently, applying sensible defaults per database engine.

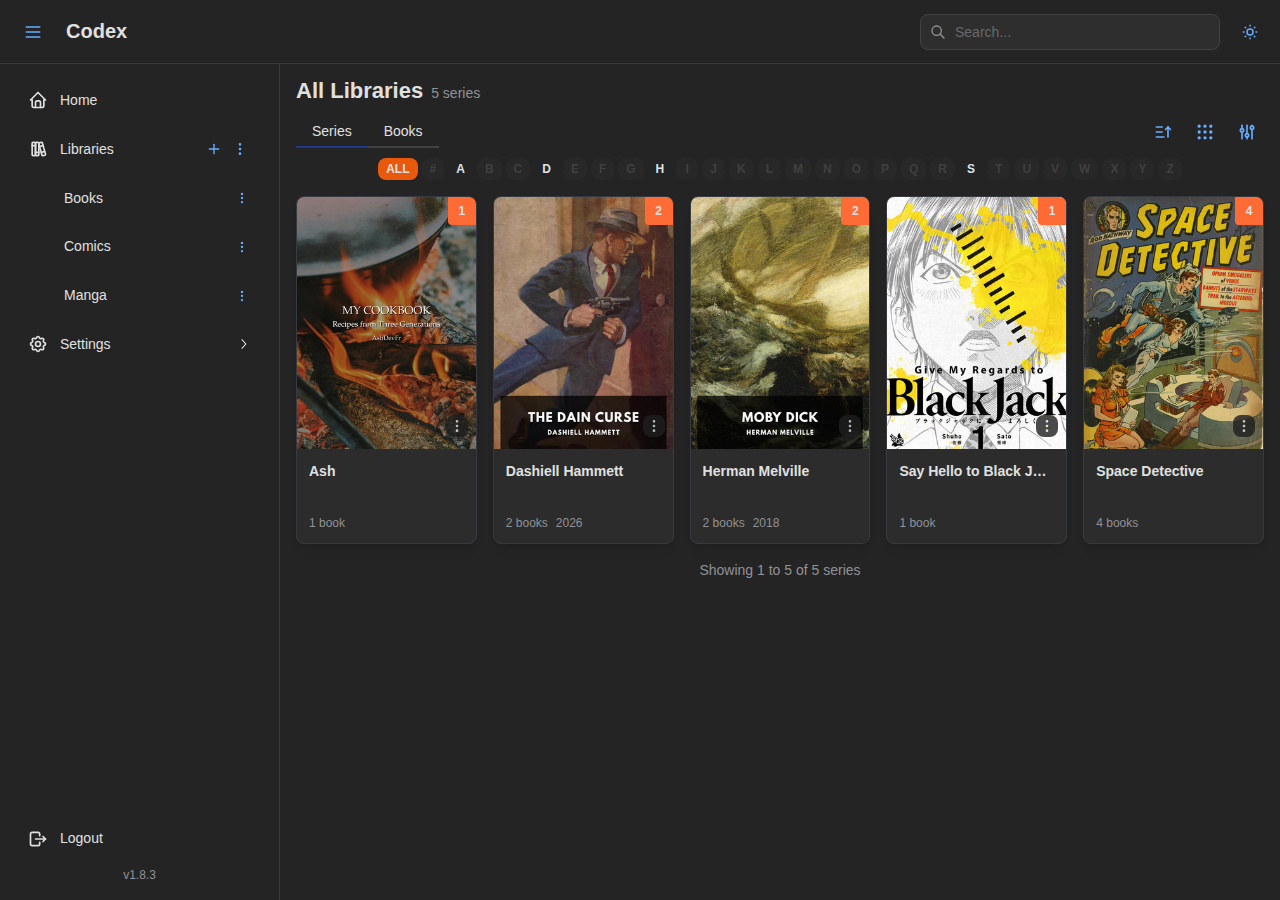

Trait-Based Scanning Strategies

One of the features I wanted most was flexible library organization. Instead of hardcoding a single “folder equals series” rule, Codex uses a strategy pattern built on Rust traits. Each library gets its own combination of a series strategy and a book naming strategy, chosen at creation time.

Series strategies include things like SeriesVolume (the classic Western comics layout), SeriesVolumeChapter (for manga with chapter subdivisions), Flat (everything in one directory), PublisherHierarchy, Calibre (metadata-driven), and Custom (user-defined regex). Book naming strategies similarly let you choose whether titles come from filenames, embedded metadata, or a combination of both.

Because these are trait implementations, adding a new strategy is just implementing a trait, not modifying a sprawling match statement somewhere.

Two-Phase Scanning

Library scanning happens in two phases. The first phase walks the filesystem, hashes files with SHA-256 for deduplication, and organizes them into series using the library’s configured strategy. This phase is fast. Your library becomes browsable within seconds.

The second phase handles the slow work: extracting metadata from file internals (ComicInfo.xml, EPUB OPF, PDF properties), generating thumbnails, and running plugin-based metadata enrichment. This runs in the background via a task queue, so you’re never staring at a loading screen waiting for a deep scan to finish.

Progress for both phases streams to the frontend in real-time over SSE, so you always know exactly where the scanner is.

Worker Separation

Codex separates the web server from background processing. In a single-instance SQLite deployment, both run in the same process. But with PostgreSQL, you can run the API server and the task workers as separate containers, scaling them independently. A busy library with thousands of books might need more worker capacity for scanning and thumbnail generation, while the API server stays lean.

Workers pick up tasks from a database-backed queue and use PostgreSQL’s LISTEN/NOTIFY to signal completion back to the web server, which then replays any accumulated events to connected SSE clients. This means real-time progress updates work even in distributed deployments without an external message broker.

Plugin System via JSON-RPC

The metadata plugin system is one of the places where the “Rust core, polyglot integrations” philosophy shows up concretely. Plugins are external processes that speak JSON-RPC 2.0 over stdio. Codex spawns them lazily on first use, communicates via structured requests, and tracks their health automatically — disabling plugins that fail repeatedly or hit rate limits.

Each plugin declares the scopes it supports (searching for books, matching series, etc.), and users configure credentials and permissions through the web UI. The protocol is intentionally simple. A minimal plugin is around 100 lines of code in any language, and there’s a TypeScript SDK to make it even easier.

Multi-Protocol API Surface

Codex exposes the same underlying data through multiple API protocols:

- A REST API (

/api/v1/) for the web frontend and third-party integrations - OPDS 1.2 (

/opds/) as an Atom XML catalog for e-reader apps like Panels, Chunky, and KyBook - OPDS 2.0 (

/opds/v2/) as a modern JSON-based catalog - An optional Komga-compatible API that lets existing mobile apps like Komic work with Codex out of the box

Each protocol is an independent router that maps onto the same service layer. Adding a new protocol doesn’t require touching the business logic — just a new set of route handlers and DTOs.

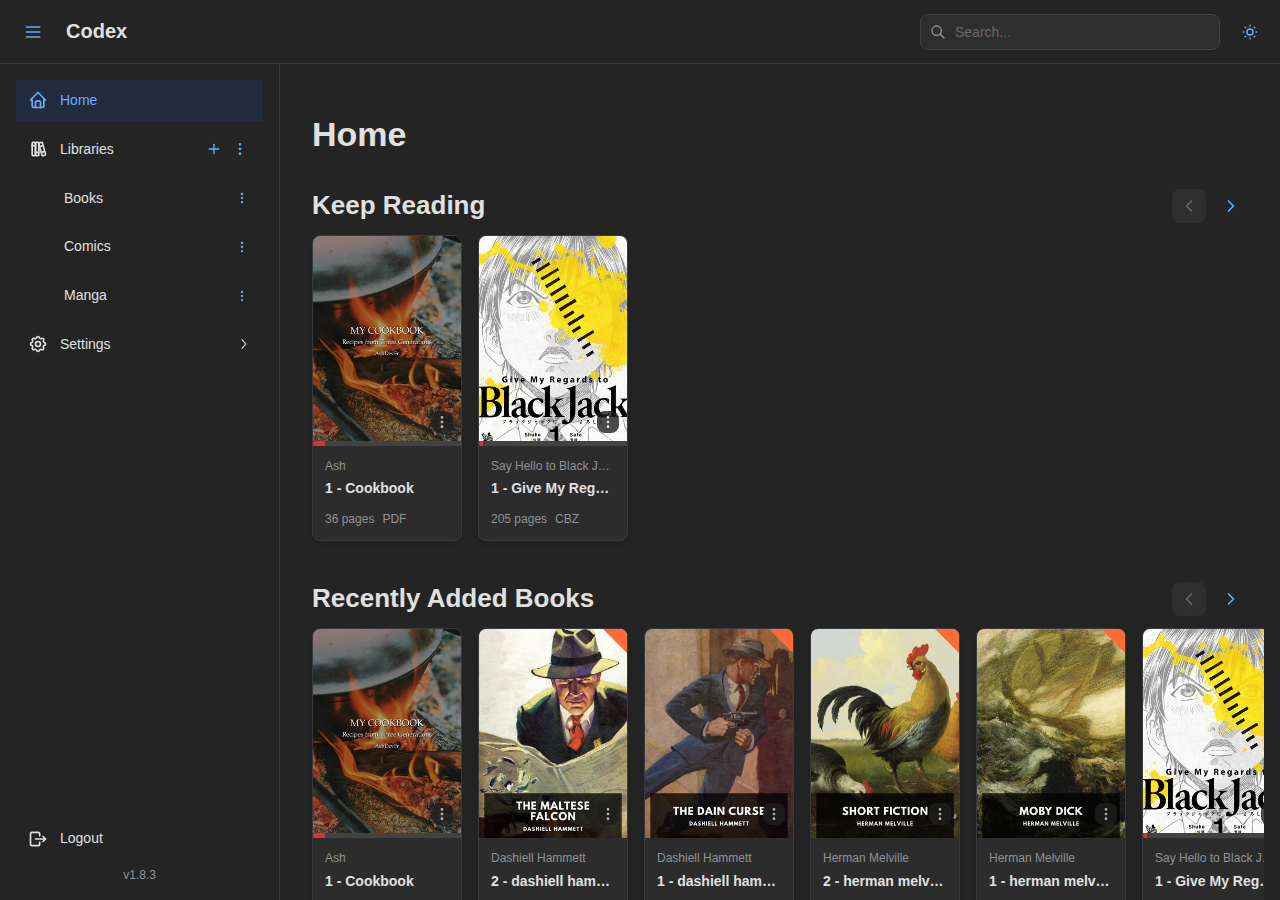

What Codex Looks Like Today

The project has come a long way from that initial CLI proof of concept. Codex now supports CBZ, CBR, EPUB, and PDF formats with full metadata extraction. It runs with either SQLite or PostgreSQL. The web UI is built with React and Mantine, featuring dedicated readers for comics, ebooks, and PDFs, real-time scan progress, and OPDS support for e-reader apps.

Some of the features I’m most proud of:

- Configurable scanning strategies at the library level, so you’re not locked into a single organizational paradigm

- A two-phase scanning system that separates fast file detection from slow metadata analysis, so your library is browsable within seconds of starting a scan

- A plugin architecture for metadata providers, with community-contributed integrations

- Dual database support from day one, with the same codebase running on SQLite or PostgreSQL

- Separate worker and server containers, so you can scale API serving and background processing independently

- A Komga-compatible API layer so existing mobile apps work out of the box

- Built-in readers for comics, EPUB, and PDF with per-series customizable settings

What’s Next

Codex is actively developed and already usable as a daily driver. The source repository isn’t public yet since I’m still working through the main roadmap, but the documentation is already live and the Docker image is publicly available if you want to give it a try.

Some of the things currently in the pipeline:

- OIDC support for single sign-on integration

- User plugins to sync with external services (for example, pushing read progress to AniList) or to power a recommendation engine that suggests what to read next based on your ratings

Sometimes the third attempt is the one that sticks.